|

|

Last Updated: Dec 15th, 2012 - 23:02:00 |

|

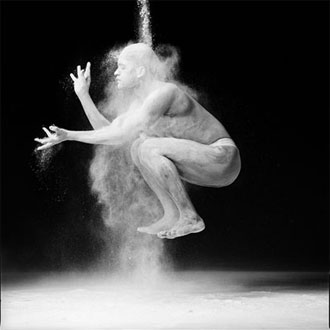

| © Lois Greenfield |

Since the 1980s, Lois Greenfield's images have made their indelible imprint on the world of dance. Her compositions of beautiful bodies frozen in space are awe-inspiring, and often spark questions like, "How did the dancers get in that position?" Her work has appeared in numerous advertising campaigns and editorial spreads, in addition to many gallery showings. Two monographs of her work are currently available--Breaking Bounds and Airborne--with a third one on the way.

|

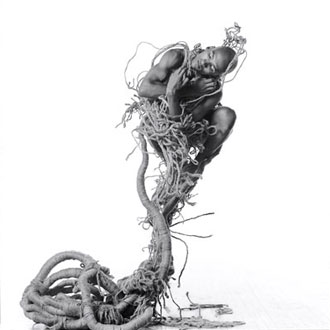

| © Lois Greenfield |

When Greenfield began taking pictures, she stated, "My dream was to be a National Geographic photographer, sparked by my travels and community service projects." She photographed a variety of subjects for alternative newspapers in the Boston area, learning her craft as she went along. After photographing a dance concert, she set about mastering the technique of capturing unpredictable movement onstage, and discovered that she was fascinated with the subject matter. She moved back to New York City in 1973, and started photographing for The Village Voice. This 20-year relationship became a laboratory to explore new and different ways to photograph dance. On assignment for The Voice in 1982, she met and photographed dancers David Parsons and Daniel Ezralow with exciting results. This ground-breaking collaboration convinced Greenfield that she preferred the ability to "shape and refine the moment as a photograph," rather than simply document what was on stage. "I tell my dancers to leave their choreography at the door," she explains. And her photographs are all single images--in other words, she never recombines the figures, nor does she use Adobe Photoshop--as many people assume.

Double Exposure: When did you first become interested in photography?

Lois Greenfield: I became interested in photography in my freshman year of college, 1966. That summer, I volunteered for a community service project in South America and took pictures with an inexpensive camera (which was a step up from the Brownie I used in high school)! I trained my lens on Indians in Ecuador, fueled also by my interest in anthropology, which became my major in college. I expected to be an ethnographic filmmaker but became a photojournalist instead. After graduation, my interest in other cultures was translated into travel photography.

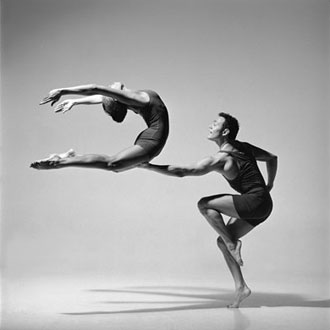

|

| © Lois Greenfield |

DE: Where did you go to school?

LG: Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts.

DE: I read that at one time, you photographed dance performances. What made you decide to photograph dancers in your studio?

LG: I started photographing dance on assignment for the newspapers I was working for. I had no interest in dance at the time, but soon discovered that I enjoyed shooting dance as much as the riots and rock stars of the early 70s. But it was very frustrating to work during dress rehearsals for many reasons. The lighting was always changing, and it was usually too dark to get good results. Secondly, the dancers weren't always in costume or dancing full out. Thirdly, you had to jostle for position with a phalanx of other photographers and hope you wouldn't run out of film during the most exciting part of the dance! Those frustrations aside, I wasn't happy merely documenting someone else's art form. I became increasingly curious about the expressive potential of movement, wanted to control the lighting with the use of strobes, and reshape the choreography. I hadn't ever studied photography, so I just started playing around. This gave way to total improvisation in the studio, and composing images that could only exist as a photograph.

|

| © Lois Greenfield |

DE: Who were your early influences?

LG: Since I had no prior interest in dance when I started photographing it, I had never explored the history of dance photography. My first exposure to a dance photographer was Barbara Morgan. I was intrigued by her work because she extracted Martha Graham and her dancers from a theatrical context, and photographed them in a photo studio. I liked the way the costumes would reveal the arc of the dancer's movement. I find myself using fabrics in my photos for the same reason: The swirls of billowing fabric is not only angelic, it depicts the passage of time itself. Dance is the ostensible subject of my work, but the subtext is time. The dancers give form to the passage of time and the camera allows us to extract 1/2000 of a second from that continuum.

With Max Waldman, I was influenced by the way he used pronounced photographic grain as a dramatic element within the picture, as though his actors and dancers couldn't extricate themselves from it. He united the medium of photography with its subject--in his case, theater. In my early work, I used the black frame (the negative's actual border), to interact dramatically with my subjects. Their improvisations play off the frame as though it were a real container. The frame often confines or radically crops them to imply entrances, exits and off-screen space.

|

| © Lois Greenfield |

Lastly--but most importantly--is Duane Michals. I was drawn to the way he made the unexpected happen in his photographs; such as having people gradually dissolve into blurs. He was more interested in the emotional resonance of an event than in the event itself. He didn't rely on the fixed moment--he would integrate the present with the past, juxtapose the dream with the reality, and speculate on the future at the same time. It was actually as much his philosophy as his work that inspired me. When I just out of college, I went to hear him speak at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In this iconoclastic lecture he said to a crowd of Minor White/Zone System enthusiasts, "If all your life means to you is water running over rocks, then photograph it, but I want to create something that would not have existed without me." Voila.

DE: Tell us about photographing motion. How do you know when to click the shutter?

LG: In dance photography, if you see the moment, you've missed it!

I always anticipate the moment. There are no rules for this; it's a matter of instinct. It's actually easy to teach someone how to capture the "peak moment." What often interests me more, however, are the split seconds before or after the so-called "peak." There are very subtle emotional nuances in these micro-moments. A dancer going up, for example, connotes striving, whereas coming down suggests release. A completely different narrative can emerge from the same series of jumps, depending on the timing. I am fascinated by these subtleties.

|

| © Lois Greenfield |

DE: What camera equipment do you use?

LG: I use a Hasselblad 500c/m camera body, with no motor drive or image reverser. My favorite lenses are the 120mm and 150mm. My strobes are Broncolor, primarily because I can set the flash duration to 1/2000 of a second or greater. To get crystal-sharp images, the duration of the flash is much more critical than the camera's shutter speed. I use a Leaf Valeo 22i digital back on my Hasselblad. When I convert a Leaf Mosaic file to black-and-white, the tonal range of the converted image equals that of film. The Leaf back also has the quickest recycle time, so I can shoot rapidly as the dancers improvise.

DE: Do you photograph models, dancers, or both?

LG: Both, depending on the job. For most part, models can't do what my dancers can.

DE: Who are your clients?

LG: Besides dance companies and Broadway theater shows, I do advertising for pharmaceutical and commercial clients such as Sony, Pepsi, Epson, AT&T, and IBM, Xerox, Rolex, etc., and editorial work for Elle, GQ, Sports Illustrated, and Vogue, among others.

|

| © Lois Greenfield |

The choreography began with a photo shoot in Adelaide, Australia. I had never worked with the company before and just created shots in my usual improvisational and collaborative way. Garry Stewart, the choreographer, then created the dance to include moments similar to the shots I took. Then frankly, all hell broke loose, as I found myself on stage during the show with digital SLRs, following the action and zooming in and out like I hadn't done in 20 years! To make it even more terrifying, every image I shoot appears within seconds on the two screens. There are photographic surprises too, with one "stroboscopic" scene and another where I walk around with a 200mm lens, shooting extremely close-up body parts as the dancers writhe around. We've performed it in Sydney, NYC, and Paris, among other locations.

Here are some words that describe "Held's" conceptual framework:

This is the first time the inner processes of photography are "dramatized" in the context of a choreographed dance piece. The performance touches on the materials, methods and optics of photography and its time-altering alchemy. By stopping time, a split-second becomes an eternity. Ironically, freezing a split-second gives the movement more solidity than it had as a fleeting gesture of dance. We know nothing in the real world can exist in two dimensions, yet photographs seduce us into believing that it is a valid representation of reality. We end up convinced we "saw" what the photographs depict, even though it was beyond the threshold of perception.

DE: Do you photograph any other subjects aside from people?

LG: I'm currently intrigued by a long-standing obsession with reflections (in the real world, not the studio!)

DE: What are your future plans?

LG: I've embarked on a feature film project with Jodi Kaplan, exploring ritual dance around the world. It won't be a documentary, but rather, an anthropologically inspired art film. Between this film and "Held," I've returned to my roots in both stage photojournalism and ethnographic filmmaking--or, as we would phrase it today--making films about indigenous cultures.

Visit Lois Greenfield's web site.

Weekend Workshop

Learn how Lois achieves her crystal-sharp images with sculptural lighting. Shoot professional dancers in Lois' studio using her Broncolor strobes which stop action at 1/2000 of a second. The group is small and good for all levels.

For workshop information:

loisgreenfield.com/eventsworkshops

This article brought to you by PHOTOWORKSHOP.COM. Let us know if you found this article useful and tell us what kinds of articles you'd like to see in upcoming issues. Send your comments and ideas to the editor.

Top of Page

|

|

| |